Pity Callahan’s Caravan. Pity, or fear it. Wherever these metal-working merchants go, somebody dies.

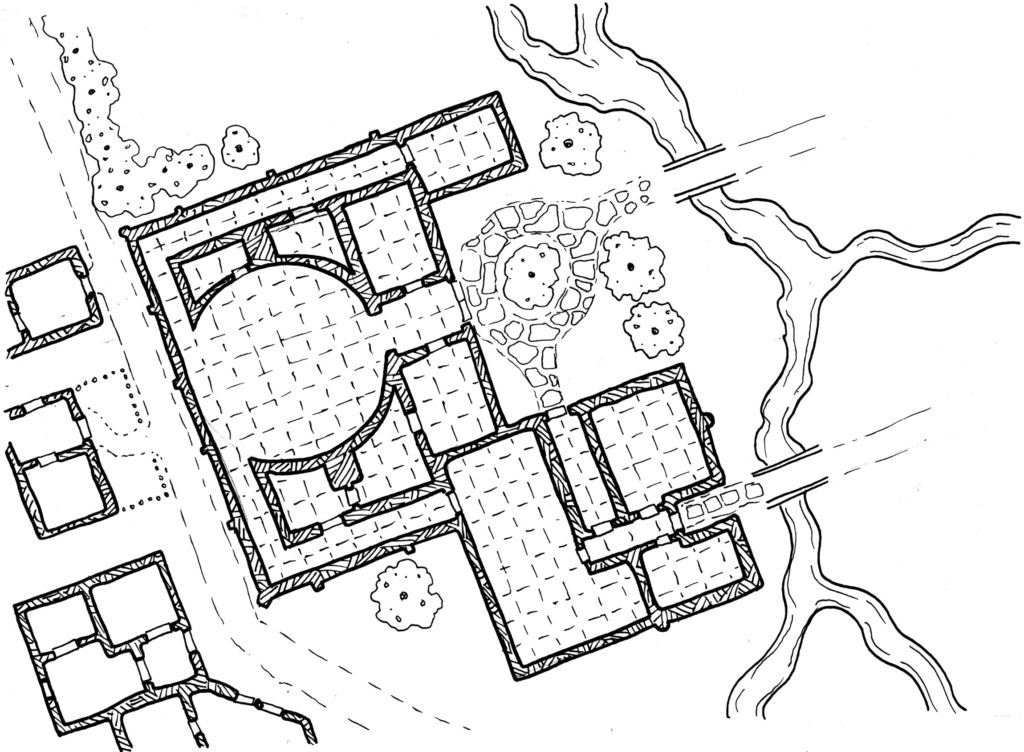

Callahan’s Caravan of Death is a faction that can be used either as a friendly ally and source of adventure, or as a foe to be fought. It consists of two dozen people (twelve adults and twelve children) spread across nine wagons. They spend the spring and summer traveling the trade routes, selling various metal objects such as pans, knives, files, and scythes, and the other half of the year in a quiet valley where they smith those objects.

As a friendly faction, the members of Callahan’s Caravan face a perplexing problem. Whenever they arrive in a town with their caravan of nine wagons and trade, within 24 hours, someone in that town dies. Sometimes it’s a grandmother on her death bed. Sometimes a person slips and cracks their head. Sometimes it’s more mysterious, like an unpopular council member dying in his sleep. Rumors have spread, and now when the caravan rolls into town few people come out to do business with its members.

Plot hook: The PCs are approached by Millicent Avernath, one of the more successful merchants and the de facto leader of the otherwise mostly democratic caravan. She asks the PCs to investigate and clear the caravan’s name. As it happens, another member of the caravan — Hossil Thrick, a haughty half-elf — angered a hag some months back by making her a shoddy kettle. The hag since cursed the caravan, causing this trouble.

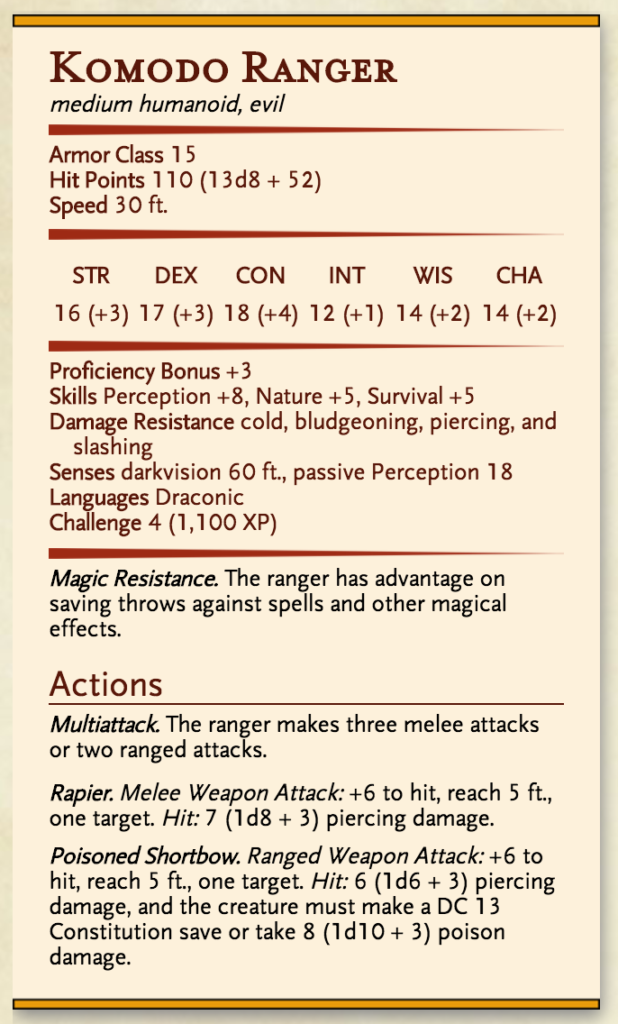

As a foe, the same situation generally applies: within 24 hours of the caravan arriving in a settlement, somebody in town dies. However, the circumstances are usually somewhat suspicious. As it turns out, the caravan has been unable to compete with other, more successful merchants, and agreed to take on a disguised assassin for a hefty fee.

Plot hook: The PCs are approached by Dar Surefoot, the half-orc who organizes the (tiny) local watch, the day the caravan enters town. He’s heard about the deaths, and want the PCs to investigate.