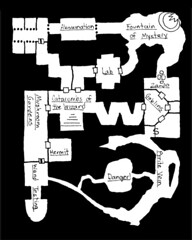

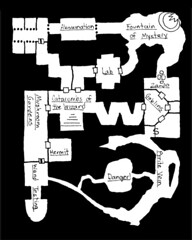

'CatacombsOfTheWizard' by orkboi on Flickr

Dungeon World is another sword-and-sorcery tabletop RPG system aiming to recapture the purity of classic Dungeons & Dragons. The surface looks the same, including the four classes of Cleric, Fighter, Thief, and Wizard. The mechanics and approach, however, are quite different.

Player-character attributes mirror D&D, except for the addition of Bond, which is used to indicate how well each character knows each other character. Moreover, at the beginning of each session, two attributes are “highlighted” by other players and the GM. If a player uses those attributes during the session, the PC gets extra XP.

The basic die mechanic is 2d6, added together, plus any modifiers. 10 or higher is a full success; 7-9 is a success with a complication; 6 or lower is a failure.

The “move,” which is the core procedure of the system, is a rule that lists a trigger (the thing in the game that activates the move), possibly a roll, and a set of possible results.

Interestingly, moves are not optional. If any character action satisfies the trigger condition for a move, the character must immediately use that move.

Moreover, moves are always responses to character actions. A player can’t say “I use the Defy Danger move;” the player must narrate a character action which triggers the Defy Danger move.

This is central to the system. Players must narrate. The mechanics must flow from that narration.

There are also mechanics that allow for results to be held for the next turn, for the next use of a move, until a condition is met, or using a currency called “hold.” The move specifies the uses of “hold.” For example, if you stand in defense of a person, item, or location under attack and succeed fully, you get 3 hold. You can later spend that hold to redirect an attack from the defended item to yourself, or halve the damage of an attack against the defended item, or deal extra damage to anything attacking the defended item.

In a reversal from traditional D&D, most weapons deal no damage themselves. Damage is dealt by rolling a certain sized die for your class, and in some cases adding +1 for a particularly powerful weapon. The system justifies this by pointing out that your class’s training determines your ability to hurt people. Thieves are not build to deal damage; they have moves that make them useful in many other ways.

Unfortunately, the rules are written with often-tortured grammar, making many sentences hard to parse. Here’s an example, and I’ve even corrected two typos: “When the doom you show signs of is an onslaught of goblin arrows, if the players don’t do something to get out of the way, you can follow through with damage as a hard move.” This is frequent enough that I needed to re-read many passages to fully understand them.

I wouldn’t mind this in a supplement, but these are the core rules.

The term “move” compounds the issue. It’s such a generic word that I often felt confused by a particular turn of phrase. When a rule tells you to “make your move,” is that meant colloquially or mechanically?

When we sat down to play it, the game progressed smoothly. I spent much of the time prompting players with “What do you do?”, as the rules demanded, which non-plussed a few players. Dungeon World expects focus, an admirable quality.

much as I’m complaining about it, I found Dungeon World‘s rules and approach refreshing and effective. We had a classic hack-and-slash adventure. It did exactly what it claimed it would do.

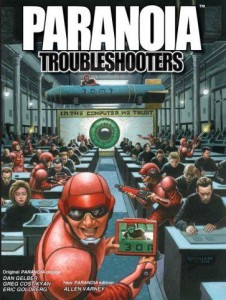

RPG players are conditioned to view PC conflict as an absolute bad. So how can I describe the fun of an RPG that assumes players will attempt to kill each other at every session?

RPG players are conditioned to view PC conflict as an absolute bad. So how can I describe the fun of an RPG that assumes players will attempt to kill each other at every session?